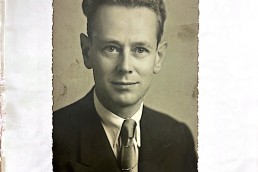

William Harrison Ainsworth was born February 1805 on King Street in Manchester (Axon, 1855). Ainsworth carried many hobbies expected of a novelist. He was deeply passionate about theatre in his younger years and even had a tiny theatre in the basement of his house.

A more peculiar obsession of Ainsworth’s as a youth was his love of pyrotechnics, more specifically the construction of fireworks (Ainsworth, 1847). It is then quite remarkable when these two interests overlapped in the form of his serialized novel, Guy Fawkes: or, The Gunpowder Treason. A Historical Romance.

Serialized in Bentley’s Miscellany from January 1840 to November 1841, Ainsworth wrote Guy Fawkes over a period of 22 months. The novel presents a heavily romanticized version of events before and after the 1605 Gunpowder Plot. The creative liberties taken in the novel have been seen by some as justifiably close enough to the historical accuracy of events (Ainsworth, 1842), though there are some very clear divergences from recorded history.

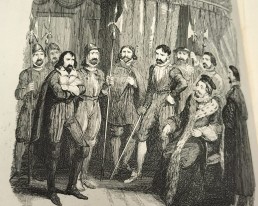

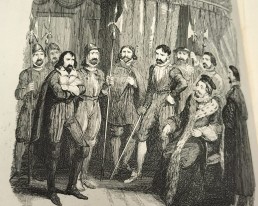

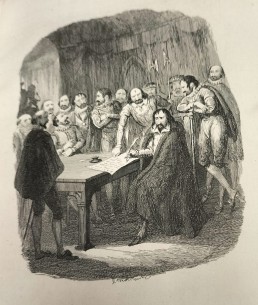

The clearest divergences stem from Ainsworth’s introduction of supernatural elements. The illustrations by George Cruikshank (beautiful and dramatic as they are) depict two key scenes to which I’d like to draw attention: John Dee ‘Exhibiting his magical skill to Guy Fawkes’ (pp. 52), and the ‘Vision of Guy Fawkes at Saint Winifred’s Well’ (Ainsworth, 1878, pp. 82) The images portray a sense of supernatural horror, even when they depict figures that aid Fawkes. The magic circle and skeleton behind the curtains portray Dee as a practitioner of witchcraft rather than his actual skills as a summoner of divine spirits (Parry, 2012). The ghostly figure in the illustration gives off an air of menace, visiting Fawkes during his sleep with the moon high in the sky, a very gothic atmosphere. Regular historical inaccuracies exist too, such as the existence of Vivianne Radcliffe, who is a completely fictional character created solely to give Fawkes and Humphrey Chetham a love interest. Ainsworth’s inaccuracies tend to serve the purpose of humanizing Fawkes. The aforementioned vision at Saint Winifred’s gives Fawkes a martyr–like role; he persists in carrying out the plot even after God gives him a vision that reveals it will fail. Characters like John Dee never met Fawkes (Chetham Library, n.a)

To give credit to Ainsworth, the inclusion of real history blends in with the historical fiction. As an example, Dee was known to have returned to London in the winter of 1604 despite supposedly being meant to stay within Manchester. Dee’s absence from Manchester in real history was caused due to financial and religious squabbles (Parry, 2012), but Ainsworth cleverly used a real time frame in which Dee was not occupied to justify his role within the story.

Critical reception of Guy Fawkes has been mixed. Steven Carver views the sympathetic portrayal of Fawkes as a possible ‘plea for religious tolerance’ (Dasgupta, 2021). Early twentieth-century critics like Francis Gribble viewed the plots of Ainsworth’s historical novels as relying too much on history to create a plot. Gribble stated that ‘In the severely historical works […] The plot is covered up by tableaus taken from Hollinshed’s and other chronicles’ (Gribble, 1905 pp. 538). Contemporary audiences from the late nineteenth century generally enjoyed the books. Guy Fawkes and its sister romance novel, The Tower of London (1840), were seen as significant boosts to Ainsworth’s reputation, although this boost could just be the result of these novels coming after Jack Sheppard (1839-40) which was massively popular.

Bibliography

Ainsworth, W.H. (1878) Guy Fawkes; or the gunpowder treason: an historical romance, George Routledge and Sons, London.

Anon. (1871) William Harrison Ainsworth. The Illustrated review: a fortnightly journal of literature, science and art, 2(28), pp. 321-323.

Axon. W. (1885) Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 197-99

Chetham Library, (n.a), John Dee Material Associated with John Dee (1527- 1608) [Online], [Available from: https://library.chethams.com/collections/101-treasures-of-chethams/john-dee/#:~:text=In%201841%20the%20novelist%20Harrison%20Ainsworth%20published%20the,that%20the%20young%20Humphrey%20Chetham%20knew%20John%20Dee.]. [Access Date: 21/03/2023]

Dasgupta, U. (2021) The Author Who Outsold Dickens: The Life & Work of W. H. Ainsworth by Stephen Carver (review). Dickens Quarterly [Online], 38(2), pp. 206-209. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2547569728?OpenUrlRefId=info:xri/sid:summon&accountid=9653. [Accessed: 21/03/2023]

Gribble, F. (1905) Harrison Ainsworth. Fortnightly review, May 1865-June 1934, 77(459), pp. 533-542.

Memoir of W. Harrison Ainsworth, Esq. (1842) The Mirror of literature, amusement, and instruction, Nov.1822-June 1847, 1(1), pp. 5-16.

Parry, G. (2012) The Arch Conjuror: John Dee. Yale University Press.

Bibliography

Colby, Robert A. (1985) “Tale Bearing in the 1890s: The Author and Fiction Syndication”. Victorian Periodicals Review. Vol.18, No.1, pp. 2-16.

Hilliard, Christopher (2009) “The Provincial Press and the Imperial Traffic in Fiction, 1870s-1930s”. Journal of British Studies. Vol.48, No.3, pp. 653-673.

Johanningsmeier, Charles (1995) “Newspaper Syndicates of the Late Nineteenth Century: Overlooked Forces in the American Literary Marketplace”. Publishing History. Vol. 37, No.1, pp. 61-82.

Jones, Aled (1984) “Tillotson’s Fiction Bureau: The Manchester Manuscripts”. Victorian Periodicals Review. Vol.17, No.1, pp. 43-49.

Singleton, Frank (1950) Tillotson’s 1850-1950: Centenary of a Family Business. Bolton: Tillotson & Son Ltd.