Every encounter with books from the Lancashire Authors’ Association Collection has a story. I missed it at first. I was brushing by the shelves looking for a book to consider mine, to write about as part of my assignment. No wonder it has been forgotten for almost one hundred years: Miss Nobody by Ethel Carnie. How many Miss Nobodies carried the world on their shoulders? So many?

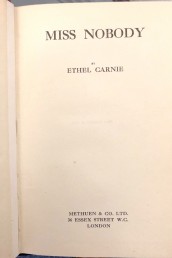

Miss Nobody, part of the LAA Collection, is a first edition, published by Methuen & Co in 1913. A review appearing in The Spectator on 3rd January 1914 summarises the novel as:

The story of a Manchester girl who marries a farmer after a very short acquaintance. The scenes at the farm of Greenmeads are prettily written, but troubles soon arise; the farmer’s sister, Sarah Gibson, makes life intolerable for the town bride, who goes off to carve out a career by herself. The account of her work in the mill and of her organizing a strike among the girls is well given, and her subsequent struggles to make a living are interesting. The book ends with the reconciliation of Carrie and her farmer and a sort of prophetic outline of their future career (Anon., 1914, p.36).

A handful of very determined people made the centenary edition possible. The editor of the new edition, Dr Nicola Wilson (University of Reading), summarises the novel’s plot as:

chart[ing] the fortunes of the independent Carrie Brown, a former ‘scullery drudge’ turned oyster shop owner from Ardwick, Greater Manchester. Schooled in the popular romances of cheap yellow-backed novelettes, Carrie decides to sell up and leave the grey city of Manchester when she receives a surprising offer of marriage from a country farmer. The plot sees Carrie struggling to reconcile herself to the ‘mixed up’ reality of marriage and the loneliness of country life, and ultimately results in her striking out on her own. The story describes Carrie’s picaresque adventures as she strives to find love and self-fulfilment in a harsh and oftentimes bitter world. (Wilson, 2013)

The Introduction is signed by Belinda Webb. One year before, in 2012, on International Women’s Day, Webb signed a fierce article in The Guardian complaining about the lack of interest in regard of promoting real working-class literature:

There are many other women writers who remain entirely overlooked, and whom present readers would doubtless enjoy and learn from. And one candidate worthy of being fished from the seas of oblivion and dragged into the literary lifeboat is Ethel Carnie Holdsworth. I fear the reason why Carnie Holdsworth hasn’t yet proved an attractive prospect for the missionary feminist is that she was trenchantly working class. Carnie Holdsworth wrote stories for and about other working-class women; women who, like herself, were already working long hours in factories and at home. (Webb, 2012)

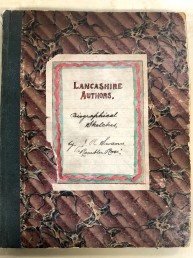

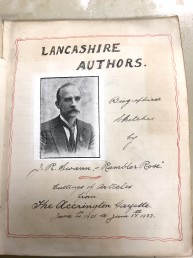

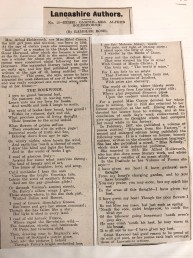

Who was Ethel Carnie? Held within the LAA Collection sits a scrapbook containing article cuttings by J.R. Swann (published under the name of Rambler Rose) taken from The Accrington Gazette (June 1921 – June 1922). One such newspaper cutting indicates that

Mrs. Alfred Holdsworth, nee Miss Ethel Carnie, the mill girl poet and novelist, was born in 1886. At the age of eleven years she commenced work ‘half-time’ as a reacher in the Delph Road Mill, Great Harwood, after which she became a winder at the St. Lawrence Mill in the same town. She was a winder for about six years. Most of her poems were conceived whilst following her employment. She manifested literary talent at quite an early age, and her first published poem was written at the age of 19, being entitled “The Bookworm”. […] In February, 1907, she published a volume of poems called “Rhymes from the Factory”, a second and enlarged edition being published the following year. It is a volume of human, homely matters, written in the clearest, simplest language. She has also published a novel, “Miss Nobody”, which deals with industrial problems.” (Rambler Rose)

Ethel Carnie’s poems have since been recorded in Lancashire, commissioned by the Pendle Radicals and in partnership the Finding Ethel project, which you can listen to, here.

To further allure you, I borrowed a fragment from one of Carnie’s poems cited in “An Assessment of Ethel Carnie” signed by Dr Kathleen Bell on Cotton Town’s website:

‘The Home Life of Factory Workers’ (The Woman Worker, March 24, 1909 p.270)

Sunday is the only day we have to live our lives. Out of the House of Bondage into the field of liberty.

They did well to allow us this one day in the week in which to have a taste of home – otherwise we should have broken loose long since.

Once I saw a picture of the crucified Christ.

That wan brow, and anguished look – you need not go into a picture gallery to see it. Stand at the gates of a cotton factory at the end of a summer’s day, and see the operatives trail out. The little half-timer by the loom, straining to reach – with thin hands throwing the shuttle, you may see it there.

Going back to the 2013 edition of Miss Nobody is worth mentioning Belinda Webb’s assessment of the novel:

Miss Nobody portrays elements of the three literary traditions that most of Carnie’s work contains: the New Woman novel, the Chartist novel, and of course, the romance. (Webb, 2013, p.xvii)

She also argues that:

In reading Miss Nobody, it is important to understand why Ethel Carnie and her work have been neglected. This has much to do with a general disdain for working-class literature, or ‘writings’, as they are commonly referred to. This demarcation between literature and writings invokes the high/low culture debate, accounting for the noticeable absence of working-class texts from ‘literary’ canons. Predisposed to melodrama, and predominantly concerned with the collective, working-class literature loses out to the bourgeois psychological journeys of the individual. (Webb, p.xv)

A review of Carnie’s book written for the lipstick socialist’s blog outlines the fact that:

Miss Nobody is Carrie Brown, an orphan, who lives in Manchester and makes a living working as an oyster seller. On a visit to her sister in the countryside she decides that life would be better there than in the city; […].

A chance encounter with a local farmer, Robert Gibson, leads to marriage and the realism that life is in the countryside was not the rural idyll she had imagined and eventually she leaves and returns to the city. (lipstick socialist, 2013)

I find this description of Carrie Brown’s husband, Robert Gibson and his sister, Sarah, absolutely delightful:

The conviction that Robert was a bit romantic were founded upon such incidents as his giving a passing tramp a copper. Sarah believed in relieving deserving cases, but had no faith in these people from nowhere, and predicted Robert’s bankruptcy and ruin every time he gave a penny.

She had a sincere affection for him, which showed itself in this curious habit of scolding at him. Perhaps there is as much affection in a good, sound scolding as in a kiss; (Carnie, 2013, p.25)

Through “The Christmas-Card Factory” chapter of Miss Nobody we have a little taste of Carnie and Carrie the activists:

By dinner-time the next day Carrie Gibson had been scolded four times. She had been inquiring once how to put in a new kind of inset, when the Eye had caught her.

“I thought”, said the purple woman, as they sat eating – “I thought you were going to go once she shouted at you.”

“I’m going now, when I’ve had my dinner,” said Carrie. “Wouldn’t work for a thing like her if it meant death on leaving. The only time she’s looked sweet was when one o’ the men came in. I hate that sort. Crushes their own sex under their heel, an’ smiles at the fellows.”

“She is a flirt”, said the pugnosed girl. “Awful!”

“If she asks for me,” said Carrie, holding the door open a moment, “tell ‘er I had enough. Tell her to keep my bob and a half, and buy herself a temper with it.” (Carnie, p.142-3)

I’ll conclude with Belinda Webb’s words:

Ethel Carnie did far more [..] compared to the middlebrow women novelists who many have championed because they once failed to make a place on the male-dominated canons. Ethel was an activist on the front lines of class and gender, and worked hard to eke out precious time to write, from the business and pressure of working in shops and factories to sustain herself in order to do so. (Webb, p.xxiv)

*Many thanks to Ewelina Chorazak for bringing to my attention Mr J.R. Swann’s articles scrapbook from the LAA Collection.

Bibliography

Anon., (1914) Miss Nobody by Ethel Carnie. The Spectator. [Online] The Spectator Archive, 3rd January, p.36. Available from: http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/3rd-january-1914/36/miss-nobody-by-ethel-carnie-methuen-and-io-6athe-s [Accessed on 03 April 2022].

Anon., (2022) Ethel Carnie Holdsworth. The Poetry Archive. https://poetryarchive.org/poet/ethel-carnie-holdsworth/ [Accessed on 03 April 2022].

Bell, K. (2017) An Assessment of Ethel Carnie. Cotton Town. https://www.cottontown.org/Culture%20and%20Leisure/Literature/Pages/Ethel-Carnie.aspx [Accessed on 03 April 2022].

Burnett, D. (2017) William Hall Burnett and the mill girl poet, Ethel Carnie. williamhallburnett.uk [Blog] 14 September 2017. Available from: http://www.williamhallburnett.uk/william-hall-burnett-and-the-mill-girl-poet-ethel-carnie/ [Accessed on 03 April 2022].

Carnie, E. (1913) Miss Nobody. London: Methuen & Co, Ltd.

Carnie, E. (2013) Miss Nobody. Kilkerran, Scotland: Kennedy & Boyd.

lipstick socialist, (2013) Book Review; Miss Nobody by Ethel Carnie. lipsticksocialist.wordpress.com. [Blog] 5 September 2013. Available from: https://lipsticksocialist.wordpress.com/2013/09/05/book-review-miss-nobody-by-ethel-carnie/ [Accessed on 03 April 2022]

Pendle Radicals. (n.d.) Ethel Carnie Holdsworth. pendleradicals.org. [Blog] Available from: https://www.pendleradicals.org.uk/pendle-radicals/ethel-carnie-holdsworth/ [Accessed on 03 April 2022]

Rambler Rose [Swann, J.R.]. (192?) Lancashire Authors. The Accrington Gazette, Lancashire Authors’ Association Collection, p.10

Webb, B. (2012) Neglected women writers: this is a class issue. The Guardian [Online]. 8th March. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2012/mar/08/neglected-women-writers-class-issue [Accessed on 03 April 2022].

Webb, B. (2013) Introduction. In: E. Carnie, Miss Nobody. Kilkerran, Scotland: Kennedy & Boyd.

Wilson, N. (2013) Miss Nobody / Ethel Carnie. flyer and back cover, reading.ac.uk, https://www.reading.ac.uk/web/files/DEAL/Miss_Nobody.pdf [Accessed on 03 April 2022]