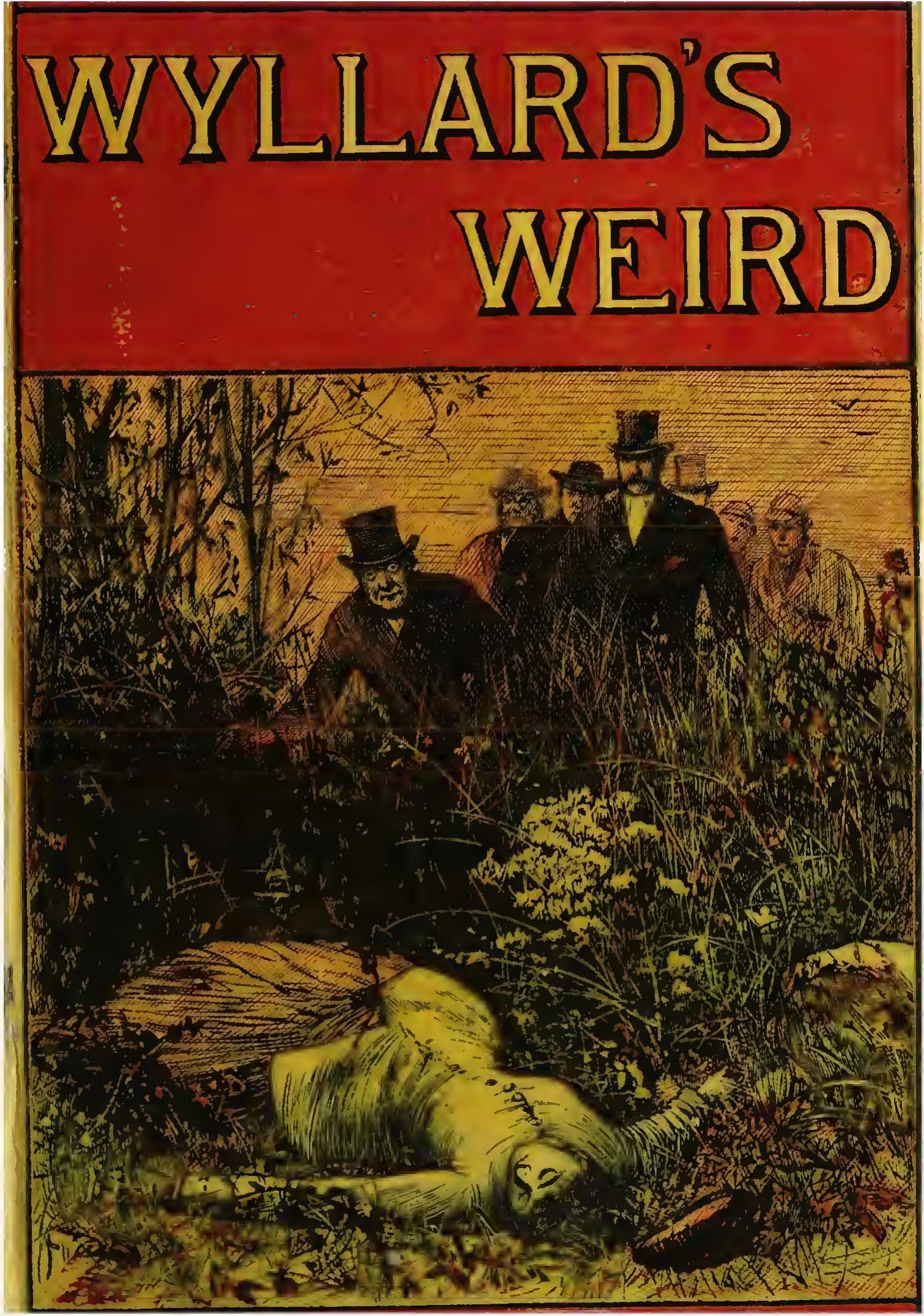

Serialised fiction in the Bolton Weekly Journal – Wyllard's Weird (1885) by Mary Elizabeth Braddon

While reading through the letters and stories from writers who contributed to the Bolton Weekly Journal in the nineteenth century, one story by Mary Elizabeth Braddon caught my attention, Wyllard’s Weird. The story’s intriguing combination of mystery, romance, and gothic literature is one of its many appealing aspects. Since it foresaw the arrival of Sherlock Holmes in 1887 and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1886, the work, which was initially published in 1885, has taken on significant literary significance (Anon., ‘Wyllard’s Weird’). This combination kept me interested in the story because it created a sense of tension and mystery surrounding the main characters’ inheritance, which made me want to find out more. Wyllard’s Weird has a very interesting character development story, with the protagonist changing as she learns more about the mysteries surrounding her family’s estate. This novel is comparable to another story written by Mary Elizabeth Braddon titled Lady Audley’s Secret (1862). The novel centres on Lady Audley and the secret she keeps hidden, whereas the protagonist of Wyllard’s Weird travels to uncover the sinister secrets of her family’s estate. The two books are distinct stories with distinct components and characters, despite possible parallels between them in terms of Gothic motifs and the investigation of secrets and riddles. The term Wyllard’s Weird, which originates from an old Scottish phrase that means “a person’s destiny,” is also utilised in the book title (Monday, 2020). It connotes something weird, unsettling, and mysterious, and it implies that the Wyllard family’s estate is peculiar or unsettling in some way.

When I came across Wyllard’s Weird in Braddon’s letters, I was taken aback because I had never heard of it before. Since it bears resemblance to one of her well-known novels, Lady Audley’s Secret, I decided to research the novel. It surprised me to learn that there hasn’t been much discussion, critique, or appreciation of the book. This is unfortunate because the book is a worthwhile read.

Wyllard’s Weird is precisely the kind of novel that Braddon, who was renowned for her ability to enthral readers with her complex narratives, compelling characters, and evocative descriptions, wrote. Her writing frequently explored issues of marriage, gender norms, and morality, went beyond the accepted boundaries of normativity by Victorian society. The fact that she discusses marriage and “the other woman” in the majority of her novels intrigues me, as she was viewed as the other woman in her relationship with John Maxwell who had been wed to Mary Ann Crowley. Wyllard’s Weird was critically dismissed by one contemporary reviewer in The Athenæum, who summarised Braddon’s mode of writing in this way:

It is obvious that current fiction is suffering from a revival. The tales of mystery and murder which went out of fashion as art came in are beginning to captivate once more, and the novel of furniture is giving place to raw tones of the romance of crime. It was not to be expected that the author ‘Lady Audley’s Secret’ should look on while others won success in the field where she had triumphed twenty years ago. ‘Wyllard’s Weird’ at all events proves that Mrs. Maxwell can still hold her own. The three-volume novelist is at some disadvantage in contending with the short stories which mark the revival. Mrs. Maxwell’s way of surmounting the difficulty is like that of the recent enterprisers of pantomime. The chief characters are doubled and the accessories are increased in splendour. One murder and one love story will do for a railway mystery, but for her three volumes Mrs. Maxwell provides two horrid murders and two love stories, and the scenery is lavishly supplied […]. Mrs Maxwell has never been very strong in the study of character. Her figures are always well described; they are good for appearance and action, but one never knows them intimately. There is no one in ‘Wyllard’s Weird’ to fascinate the reader by his personality. (1885, pp. 371-72)

The novel explored themes that remained of fascination to her readers, focusing on the scandalous and sensational. As another contemporary reviewer in The Academy tellingly noted, ‘It would almost seem as if the author of Lady Audley’s Secret had written Wyllard’s Weird to prove that her hand has not lost the cunning which first gained her popularity.’ (1885, p. 201).

Bibliography

Anon. (1885) New Novels. The Academy. 21 March, 672, pp. 201-02. [Online] Available at: <https://www.proquest.com/britishperiodicals/docview/8214148/C6B9F11E1316475FPQ/5?accountid=9653&sourcetype=Historical%20Periodicals&imgSeq=1> [Accessed 22 April 2024].

Anon. (1885) Novels of the Week. The Athenæum. 21 March, 2995, pp. 371-73. [Online] Available at: <https://proquest.com/britishperiodicals/docview/9123500/C6B9F11E1316475FPQ/1?accountid=9653&sourcetype=Historical%20Periodicals&imgSeq=1> [Accessed 22 April 2024].

Anon. (n.d.) Wyllard’s Weird. GoodReads [Online] Available at: <https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1850204.Wyllard_s_Weird> [Accessed 23 March 2024].

Braddon, M. E., (1886) Wyllard’s Weird: A Novel. London: J. and R. Maxwell.

Monday, M. (2020) Wyllard’s Weird. GoodReads [Online] Available at: <https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1850204.Wyllard_s_Weird> [Accessed 23 March 2024].