In 1842, a 'Most extraordinary case of poisoning' was reported in the Liverpool Mercury when Elizabeth 'Betty' Eccles of Bolton, was charged 'with the wilful murder of William Eccles, Alice Haslam, and Nancy Haslam, the former her step-son, the latter her own children.'

But Eccles, ‘in a firm tone of voice, pleaded not guilty’ at her trial on Tuesday 4th April 1843 (Bolton Free Press, 8 April 1843, p. 2). The court heard how Eccles had ‘a large family’, but ‘all of whom were now dead’, Alice having died just three weeks before 15-year-old William (Bolton Free Press, 8 April 1843, p. 2). Witnesses testified that they became suspicious of Betty when she attempted to quickly secure funds from the burial society associated with William’s work at a factory, of which Betty was the beneficiary. She had previously attempted to obtain money following the death of Alice, but had been unsuccessful, as Alice Hallam, her own biological child, did not work at the factory nor was she a child of an employee, unlike William.

Having previously ‘enjoyed good health’, William’s sudden death prompted a medical examination revealing arsenic to have been present in his stomach (Bolton Free Press, 8 April 1843, p. 2). Whilst this is absolutely the most widely reported account of Betty’s crime, it should be told that she likely murdered all of her children: “The bodies of her children (six, we believe) were disinterred, and arsenic was found in the stomachs of three” (Stuart, 1843). Other witnesses recalled how Betty had recently obtained poison prior to their deaths: ‘I want a pennyworth of arsenic, if you will let me have it’, Eccles said to Richard Barlow, ‘apprentice to Mr. Moscrop, of Folds-road, Bolton, a druggist’ (Bolton Free Press, 8 April 1843, p. 2). Insisting she purchase the poison with a witness, Eccles returned undeterred ‘about half an hour’ later with ‘a female, who was a stranger to me’, said Barlow.

The jury retired, ‘and, after an absence of an hour and a half, returned to the court’. Elizabeth Eccles was found guilty of poisoning and the murder of her stepson, William Eccles. Sentenced to death by hanging, Eccles ‘heard her sentence with firmness; and, at its conclusion, she clasped her hands, and exclaimed I ask for mercy, my lord.’ To which the Judge replied, ‘Oh, that cannot be obtained’ (Bolton Free Press, 8 April 1843, p. 2).

The dehumanisation of executed criminals throughout history has been rampant, from the deaths of powerful members of the royal family to infamous highway men, they have by and large been treated as forms of entertainment and spectacle. Although capital punishment had been made a more private affair by the mid-Victorian period, the enjoyment and excitement these executions raised did not stop even in Bolton.

Her execution at Kirkdale Gaol is covered rather extensively, but in an incredibly dramatized and ‘entertaining’ way. A reporter for the Bolton Free Press described the carnivalesque environment at her execution on May 6th, 1843:

At an early hour scores of persons, chiefly of the lowest ranks, composing most grotesque groups of men, women, and girls and boys, married men and their wives, swains with their sweethearts, and sailors, with companions of questionable character, were on the way to Kirkdale. By nine o’clock, there would be two thousand persons near the gaol and in the adjoining field. A considerable number of policemen were in attendance to preserve order, which they were able to effect, with comparatively little trouble, considering the motely assemblage they had to manage. Very few seemed impressed with serious feeling. Men and youths were jumping, youths and young women gallanting, and boys and girls laughing and romping. On the way stood a person with nuts and gingerbread, and a gambling board. […H]undreds and hundreds arrived on foot, and in vehicles of all shapes and kinds (Bolton Free Press, 13 May 1843, p. 4).

Eccles was hung alongside William Buckley in front of a crowd of ‘not […] fewer than 20,000 to 30,000 persons’ where ‘several women fainted’ (13 May 1843, p. 4). In contrast to Buckley’s polite and open demeanour before their deaths, Betty was “altogether more reserved in her manner and less communicative in her thoughts than the male culprit” (Anon). She did, however, make a full confession of poisoning William Eccles, ‘but denied murdering the other children’ (Bolton Free Press, 13 May 1843, p.4). Coming up to her hanging, she showed no significant emotion or distress, but her death was not a quick nor painless one. Showing remarkably little empathy, the recollection of her final moments describes her as “(Struggling) convulsively for some time, but at length she also swayed to and fro in the wind…” (Anon, The Execution of Betty Eccles).

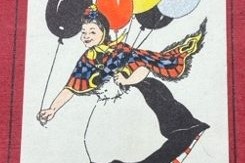

In a move common at the time, but completely out of the question today, a ‘broadside ballad’ was composed and attached to further describe her death and crime, dehumanising and strangely jovial. It can be seen on the right.

To add to the idea of spectacle surrounding her death, a wax or plaster cast was made of her head and kept with plans of adding her to a museum or display exhibit. The wax work exhibition displaying ‘at considerable expense’ a ‘correct Likeness [sic] of BETTY ECCLES’ was advertised in The Bolton Chronicle, for which admission for ‘working people and servants’ had been reduced to ‘2d’ and ‘Children under 12 years, only 1d. each’. The likeness was also mentioned in The Journal of Health and Disease from 1848.

Bibliography

Anon. (1883) A Woman Charged with Poisoning [Illustration]. The Illustrated Police News. [Online] 20 October, p.1. Available from: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000072/18831020/002/0001 [Accessed 2 April 2025].

Anon. (1843) Admission reduced at the Wax Work Exhibition [Advertisement]. Bolton Chronicle. [Online] 29 July, p. 2. Available from: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001291/18430729/019/0002 [Accessed 30 March 2025].

Anon. (1842) Most Extraordinary Cases of Poisoning. Liverpool Mercury. [Online] 7 October, p. 8. Available from: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000081/18421007/037/0008 [Accessed 30 March 2025].

Anon. (1843) The Condemned Criminals at Kirkdale. Bolton Free Press. [Online] 13 May, p. 4. Available from: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003148/18430513/046/0004 [Accessed 30 March 2025].

Anon. (n.d.) The Execution of Betty Eccles. Nottingham. Available from: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Elizabeth_Eccles_the_Female_Monster_who/rVRhIJg3KX0C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=elizabeth+eccles+murder+bolton&pg=PP11&printsec=frontcover [Accessed 26 March 2025].

Anon. (1843) Wilful Murder of Children at Bolton. Bolton Free Press. [Online] 8 April, p. 2. Available from: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003148/18430408/020/0002 [Accessed 26 March 2025].

Stuart, J. (1843) The Charleston Mercury. [Online] 9 May. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=GGJiAAAAIBAJ&pg=PA2&dq=betty+eccles&article_id=5928,4418551&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjigIe90pOMAxU08rsIHZakKoAQ6AF6BAgLEAM#v=onepage&q=betty%20eccles&f=false [Accessed 26 March 2025].

The Journal of Health and Disease (1848). London: Sherwood & Co. Available from: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Journal_of_Health_and_Disease/eVEFAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1 [Accessed 26 March 2025].