The Lancashire Authors’ Association (LAA), is a group of Lancashire Authors dedicated to studying and promoting Lancashire literature, history, dialect and traditions. The group first formed in 1909.

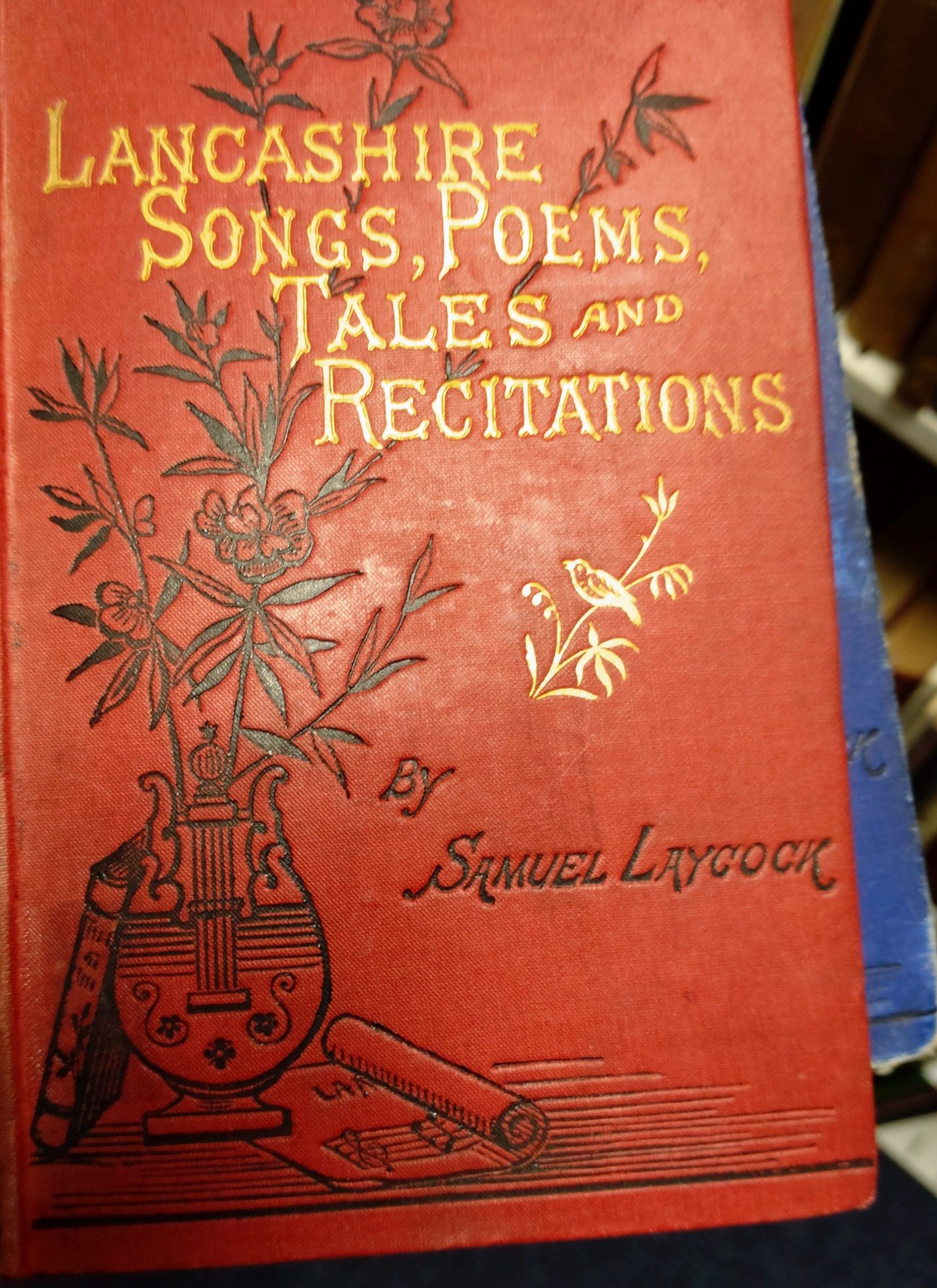

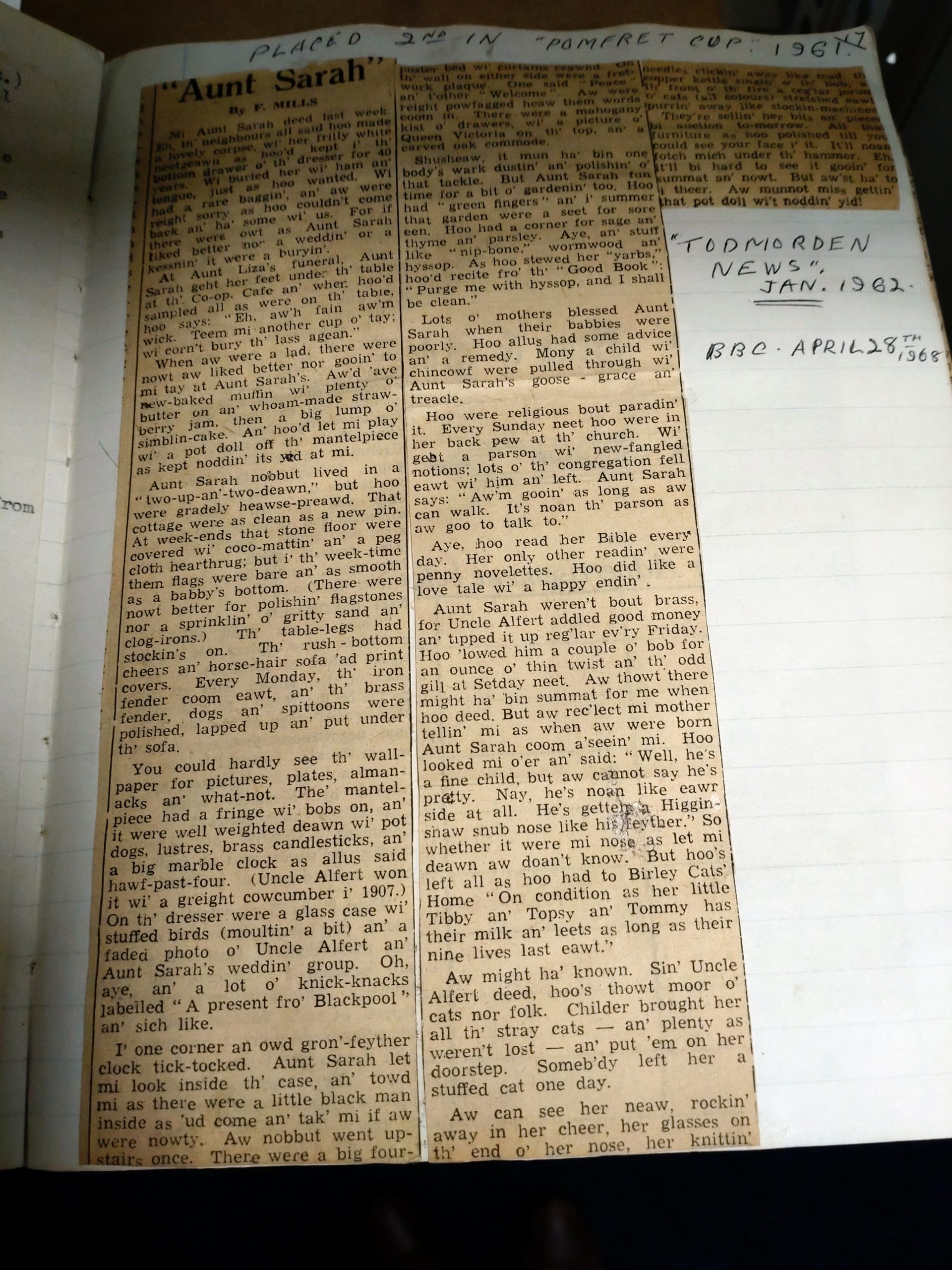

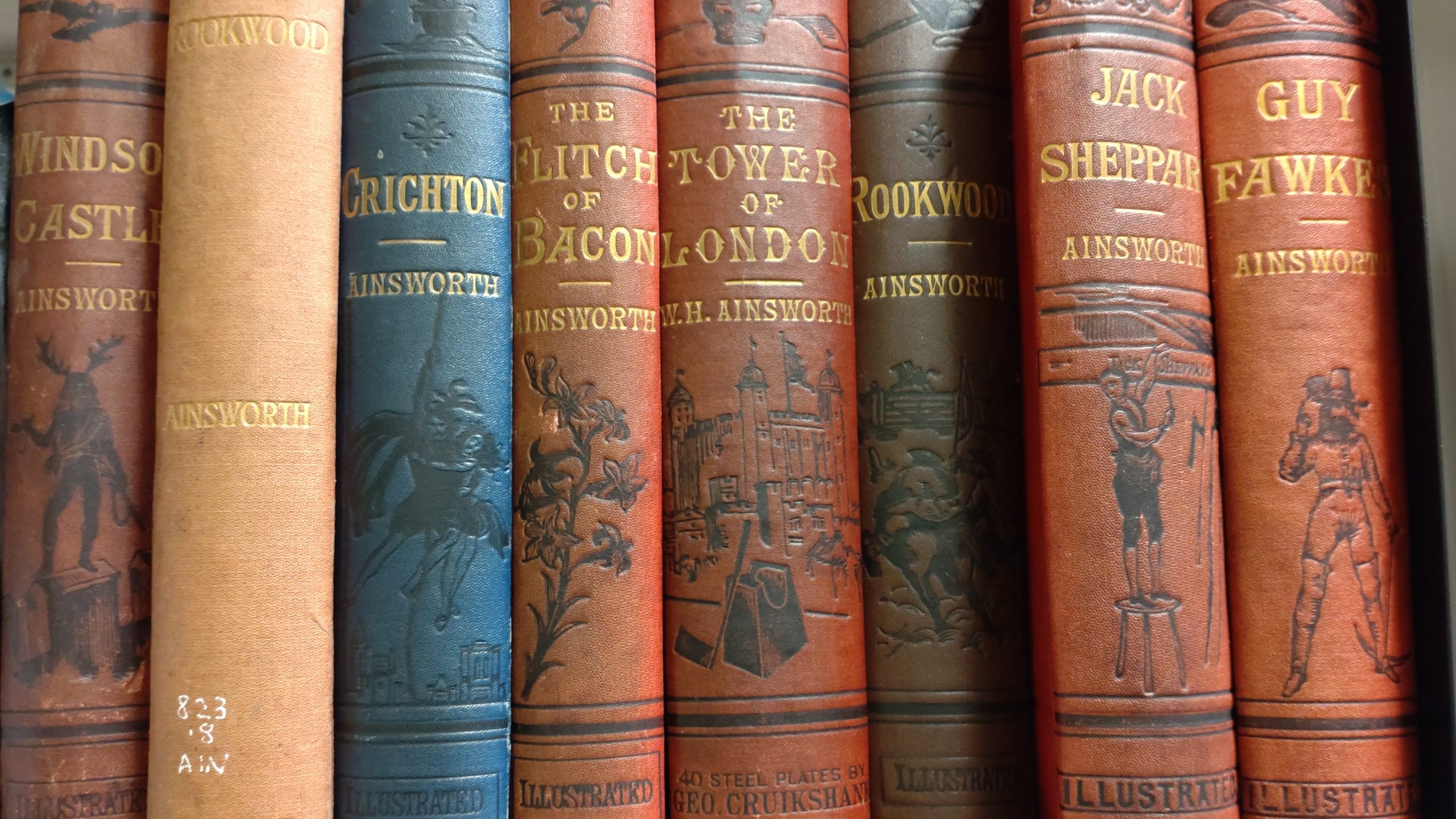

Their Library consists of over 2000 volumes, and from 2021, its centenary year, is housed at the University of Bolton. The collection of books is as variegated as it gets: novels, poems, pieces of history, periodicals, dialect studies, local songs, ballads, and legends, journals, unpublished writing, scraps from newspapers about Lancashire authors, in one word – a treasure. It was really hard to choose just one book so, I start with a dictionary.

I am a Romanian adopted by the Lancashire dialect through marriage. A dictionary should enlighten me about what I got myself into. James Orchard Halliwell’s Dictionary of Archaisms and Provincialisms – Obsolete Phrases, Proverbs, and Ancient Customs, from XIV Century is not just a dictionary but a collection of old texts, references to well-known authors and books, memories, and good old humour. The author couldn’t have been more controversial even if he had tried. On Folgerpedia, J.O. Halliwell is presented as

“an antiquarian, literary scholar, and major collector of Shakespearean works and related documents. Born James Orchard Halliwell, he acquired the surname Phillipps in 1872 following the death of his father-in-law, Sir Thomas Phillipps. The bulk of his collection is now at the Folger. […] Halliwell began collecting while still at William Henry Butler’s school in Brighton. By 1839, at the age of 19, Halliwell had become a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and published his first pamphlet on collecting, A Few Hints to Novices in Manuscript Literature.” (Folgerpedia, 2022)

However, Halliwell was accused by his father-in-law of stealing a rare 1603 quarto Hamlet. The story is registered in Eric Rasmussen’s book The Shakespeare Thefts, In Search of the First Folios. In 1845, Halliwell was one more time accused of removing some valuable manuscripts from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. During his work as a researcher, some librarians also accused him of mutilating old books to create his own scrapbooks. In their essay “Did Halliwell Steal and Mutilate the First Quarto of Hamlet?”, Arthur and Janet Ing Freeman try to exonerate Halliwell from the thefts and praise his work as a scholar. His dealing with books remained questionable.

Between 1846 and 1847, Halliwell published A Dictionary of Archaic & Provincial Words, Obsolete Phrases, Proverbs & Ancient Customs, From the Fourteenth Century, in two volumes. To give you a taste of his findings, I’ll reproduce the first stanza of the “Hymn to the Virgin” from Henry III’s, part of the chapter dedicated to the “Specimens of the Early English Language”:

Blessed beo thu, lavedi,

Swete flur of parais, moder of milternisse;

Thu praye Jhesu Crist thi sone, that he me i-wisse,

Thare a londe al swo ihe beo, that he me ne i-misse.

(Halliwell, 1924, p.957)

Referring to the effort engaged in putting together the “Dictionary of the Early English language”, Halliwell admitted that it was “a work requiring such extensive and varied research, that the labours of a century would still leave much to be added and corrected, and one which has been too often abandoned by eminent antiquaries for failure to be conspicuous.” (Halliwell, p.1). Some of the more than 50000 words never appeared in any other work before. Just to prove how meticulous his work was, I’ll mention just the word “tuly” but you’ll find more incredibly rich explanations and specifics in the pages photocopied from the volume in question.

TULY. A kind of red or scarlet colour. Silk of this colour is often alluded to, as in Richard Coer de Lion, 67,1516; and carpets and tapestry, Syr Gawayne, pp.23, 33. In MS. Sloane 73, f.214, are directions “for to make bokeram, tuly, or tuly thred, secundum Cristiane de Prake in Beme.”

I schel the yeve to the wage

A mantel whit so melk,

The broider is of tuli silk,

Beten abouten with rede golde. Beves of Hamtoun, p.47. (Halliwell, p.894)

His assessments of the local dialects are as well documented:

The dialect of Lancashire is principally known by Collier’s Dialogue, published under the name of Tim Bobbin. A glossary of the fifteenth century, written in Lancashire, is preserved in MS. Lansd. 560, f.45. A letter in the Lancashire dialect occurs in Braithwaite’s Two Lancashire Lovers, 1640, and other early specimens are given in Heywood’s Late Lancashire Witches, 4to. 1634, and Shadwell’s Lancashire’s Witches, 4to. 1682. The glossary at the end of Tim Bobbin is imperfect as a collection for the county, and I have been chiefly indebted for Lancashire words to my father, Thomas Halliwell, Esq. Brief notes have also been received from the Rev. L. Jones, George Smeeton, Esq., and Mr. R. Proctor. The features of the dialect will be seen from the following specimens; o and ou are changed into a, ea into o, al into au, g into k, long o into oi, and d final into t. The Saxon termination en is retained, but generally mute. (Halliwell, p.xxii)

Here is just a sample of the old local dialect from “A Lancashire Ballad” chosen by Halliwell:

“Now, aw me gud gentles, an yau won tarry,

Ile tel how Gilbert Scott soudn’s mare Berry,

He sound’s mare Berry at Warikin fair;

When heel be pade, hee knows not, ere or nere.” (Halliwell, p.xxiii)

Because the sound is music for the ears, I’ll leave with you a link to a moment from the National Dialect Festival:

…and a link to a more modern approach, a moment from a Peter Kay Show at the Albert Halls in Bolton:

Instead of any conclusion, I’ll invite the great Nietzsche to share some wisdom with us:

Take a look at the periods in the history of a people in which the scholar comes to the fore: they are times of exhaustion, often of twilight, of decline – the overflowing strength, the certainty of life, the certainty of the future are things of the past.

(Nietzsche, p.129)

Bibliography

Edwards, Ernest. (1863) James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps. Lovell Reeve & Co, Retrieved from National Portrait Gallery, London. <https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/use-this-image/?mkey=mw128284> [Accessed 22 March 2022].

Folgerpedia, “J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps”, [Online] Available at: <https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/J.O._Halliwell-Phillipps#Scrapbooks> [Accessed 21 March 2022].

Freeman, Arthur and Janet Ing. (2001) Did Halliwell Steal and Mutilate the First Quarto of Hamlet? The Library, 2(4), p.349-363, Oxford Academic [Online] Available at: <https://academic.oup.com/library/article/2/4/349/1123052?login=true> [Accessed 21 March 2022].

Halliwell, James Orchard. (1924) Dictionary of Archaisms and Provincialisms – Obsolete Phrases, Proverbs, and Ancient Customs, from the XIV Century. 7th ed. London: Routledge.

Lancashire Authors’ Association. (2022) Lancashire Authors’ Association. [Online] Available at: <http://www.lancashireauthorsassociation.co.uk/index.html> [Accessed 21 March 2022].

Nietzsche, Friedrich. (1998) On the Genealogy of Morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rasmussen, Eric. (2011) The Shakespeare Thefts: In Search of the First Folios. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Online] Available at: <https://archive.org/details/shakespearetheft0000rasm> [Accessed 21 March 2022].