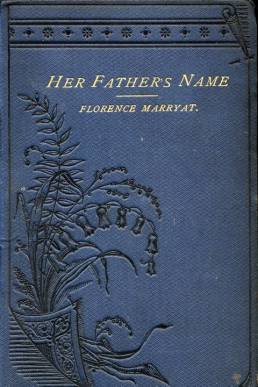

Serialised fiction in the Bolton Weekly Journal – Her Father's Name (1876) by Florence Marryat

As soon as I saw the name Florence Marryat, I was reminded of a story I read as a pre-teen, Children of the New Forest (1847), by Captain Marryat, who I was moderately surprised to discover was her father. Catherine Pope’s website, dedicated to Florence Marryat, states that she was born the ninth of eleven children to the Captain, though sadly her parents separated when she was a small child and her education was undertaken through a series of private tutors/governesses and with reference to the wide-ranging library in her father’s house (2021). After marrying in the Far East in 1854, she had by 1860, given birth to three children, was pregnant with a fourth, had survived a nervous breakdown and returned to England, leaving her army officer husband in India (Pope, 2021). She wrote first to distract her from melancholy and second to improve the financial prospects for herself and her children, completing sixty-eight novels during her working life. Nicole Morley in the Metro reports that Charles Dickens had some apparently patronising male advice for the young female author in 1860:

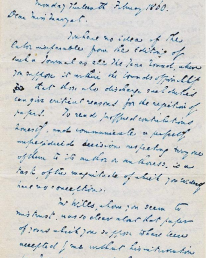

In a rejection letter, following the submission of a short story to Dickens’s periodical, All The Year Round, he berates Marryat for being ‘scarcely reasonable’ in requesting a critique of her writing. Dickens dismisses her work as ‘not-suitable’, adding that she has ‘no ideas of the labour inseparable from editing such journals as All The Year Round’ (Morley, 2016). Dickens wrote to Marryat that:

“You ask me to pass my pen over the paragraphs which displease me. Surely that is scarcely reasonable. I do not think it is a good story. I think its leading incident common-place, and one that would require for its support some special observation of character, or strength of dialogue, or happiness of description. I do not find any of these sustaining qualities in it. I am not interested in the young people, therefore, and I cannot put away from myself the unfortunate belief that the readers of All The Year Round would not be interested in them” (13 February, 1860).

This was not an auspicious critical beginning and indeed, Florence would continue to elicit responses of alarm from critical reviews throughout her life, particularly about abuse in marriage, alcoholism and adultery. Catherine Pope comments that:

Marryat rejected accusations of sensationalism, maintaining that she wrote from experience. It is no wonder, therefore, that her marriage broke down and she separated from her husband (2021).

Sarah Lennonx wrote in 2018 of Marryat’s celebrity status that her dedication to her work as actor, performer, opera singer, editor and that these talents made her popular enough to tour the U.S.A., as well as Britain, reading her work to fans everywhere. She talks about her continuing her father’s legacy and it is an interesting interpretation, given that Florence wrote a biography of him. Despite Dickens’s rather cruel comment, she survived to become a fans’ favourite.

Novel writing and particularly the sensation style was viewed by some Victorians as a sinister influence. The increasing popularity of the genre led an anonymous critic in the Westminster Review to warn that “a virus is spreading in all directions” (October 1866, p.269, qtd in Fantina p. 11). Other critics viewed sensation fiction as responsible for many perceived faults in the ‘younger generation’, rather as computer gaming is viewed by today’s ‘older generation’. An 1887 report of the Canterbury Catholic Literary Society meeting in the New Zealand Tablet revealed one speaker’s opinion:

“Mr. Cooper next painted in most forcible language the corruption existing among the youth in both sexes in America, which corruption he said is the result of novel-reading; and that young persons instead of novels should read books on church and secular history as well as works on arts and sciences” (Anon, 14 October, 1887).

Other speakers refuted his allegations, using Mary Elizabeth Braddon as an example who “had herself declared, that her reason for writing novels was to improve the human race” (Anon, 14 October, 1887). These wild claims on either side surely demonstrate the reasons for Tillotson demanding that his authors produce work suitable for family consumption (Hilliard, 2009). Pope’s observation that Marryat was writing from experience would imply that she herself was highlighting unpleasant experiences she suffered at the hands of her husband through the sensational stories she wrote. From this, it is not illogical to speculate that Florence was doing her bit for women’s emancipation, whilst supporting her family and living life to the full, without a man to hinder her.

In the British Newspaper Archive, there is evidence to deduce that the circulation of Her Father’s Name, first serialised in the Bolton Weekly Journal (March to September, 1876), was predominantly circulated in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Northern England (Peebles; Aberdeen; Belfast, and Sheffield). I wonder, therefore, if we might speculate at an aversion to sensation fiction in Catholic society, which could well be something that would be interesting to pursue further.

Bibliography

Anon, 1887. Canterbury Catholic Literary Society. New Zealand Tablet [Online] 15(25) 14 October, p. 7. Available at:<https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/NZT18871014.2.7?end_date=31-12-1901&items_per_page=10&page=21&query=fiction&snippet=true&start_date=01-01-1861> [Accessed 22 March 2021].

Dickens, C. (1860) Dickens to F. Marryat, 13 February. [Letter-online] Available at: <https://dickensletters.com/letters/florence-marryat-13-feb-1860> [Accessed 24 March 2021].

Fantina, R. (2010) Victorian Sensational Fiction: The Daring Work of Charles Reade. New York: Palgrave.

Fraser, L. (2002) To Tara via Holyhead: The Emergence of Irish Catholic Ethnicity in Nineteenth-Century Christchurch, New Zealand. Journal of Social History [Online] 36(2), pp. 431–458. Available at: <www.jstor.org/stable/3790117> [22 March 2021].

Hilliard, C. (2009) The Provincial Press and the Imperial Traffic in Fiction, 1870s-1930s. Journal of British Studies [Online] 48(3), pp. 653–673. Available at: <www.jstor.org/stable/27752574> [Accessed 22 March 2021].

Lennox, S. (2018) She was a brave and a busy woman”: Rediscovering Florence Marryat, Victorian novelist, spiritualist, and performer. Literature Compass [Online] 15(3). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12439> [Accessed 22 March 2021].

Marryat, F. (1876) Her Father’s Name: A Novel. London: Tinsley Brothers. [Online] Available at: <https://archive.org/details/herfathersnamea02marrgoog/page/n6/mode/2up> [Accessed 24 March 2021].

Marryat, F. (1883) Her Father’s Name: A Novel. London Groombridge and Sons. [Online] Available at: <http://womenwriters.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/toc.php?id=fmherfa> [Accessed 27 March 2021].

Morley, N. (2016) Charles Dickens sent this sassy reply to a wannabe writer. Metro [Online] 6 March. Available at: <https://metro.co.uk/2016/03/06/charles-dickens-sent-this-sassy-reply-to-a-wannabe-writer-5736987/> [Accessed 20 March 2021].

Pope, C. (2021) Florence Marryat (1833-99) – novelist, playwright, actress, singer, spiritualist. [Online] Available at: <https://florencemarryat.org/> [Accessed 21 March 2021].

Weger, A. (mid nineteenth century) Florence Marryat. [Online] National Portrait Gallery. Available at: <https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw80756/Florence-Marryat> [Accessed 21 March 2021].