It is notable that the Tillotson’s actually refused to publish Hardy’s most infamous work Tess of the D’Urbervilles when they received a copy of the first section in 1889, on the basis that it was “blasphemous and obscene” (Brandwood, 2019).

They promised in their 1894 prospectus “universal acceptability” (Tillotson programme for 1894), as Christopher Hilliard highlights, they wanted to be “congenial to different demographics” and the company was thereby keen to maintain a sensitivity to morally suspicious themes (Hilliard, 2009, p.665).

A Changed Man does indeed cover topics comparable to those of Tess of the D’Urbervilles, but without the exacting additions of immorality and corruption that encompass the latter, rendering it more favourable to the masses. Yet Hilliard also highlights that serials which were “thrilling to young males but boring or repellent to women were not suitable for audiences defined by locality” (p.665-666), a belief that no woman wishes to read about the relentless cruelty another woman experienced nor her presumed senseless misdeeds may explain the aversion to Tess of the D’Urbervilles, but the acceptance of A Changed Man.

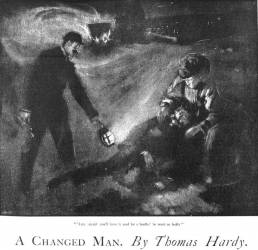

And A Changed Man does contrast Tess in some ways, too. The emphasis Hardy places on Fate and Providence in Tess of the D’Urbervilles juxtaposes his focus on the presence of the supernatural in A Changed Man, where eerie situations inject an almost harrowing darkness. Yet in other aspects the tales that make up the twelve stories of A Changed Man echo numerous themes and situations the characters of Tess find themselves in. Multiple of its stories are deemed tragic romances – both feature a socially mismatched couple who are destined to be together, but find instead that the happiness of their marriage is condemned by the imminent threat of the past. Themes of class divides, love triangles and the pastoral are littered between both – the titular character of What the Shepherd Saw, an uneducated, ingenuous boy paid to keep his silence, is potentially reflected in Tess’s personality. Reviewed in The Academy in 1913 when all twelve stories of A Changed Man were published together, the critic corroborates that readers are driven to consider the stories’ existence as “Wessex romances” (The Academy and Literature, 1913, p.592) as a result of their complicated plots, and the “accumulated mishaps that bring promising love-stories to tragic conclusions” (p.592). This review further emphasises the similarities between Hardy’s two tales by stating that Hardy “once again… frowns down the possible happy ending[s], and plunges many of his sweethearting couples into depths of gloom” (p.592).

Undeniably, The Romantic Adventures of a Milkmaid mirrors the events of Tess of the D’Urbervilles distinctly. It can be summarised as follows: a milkmaid, promised to an honest suitor, has her head turned by a foreign baron who, in a night of events not dissimilar to that of Cinderella, whisks her away to a ball where she is dressed in the finest of dresses and goes by an inconspicuous name. Anyone familiar with Tess of the D’Urbervilles will see echoed here the story of the eponymous character, similarly tempted by wealthy Alec and whisked away into a life where she becomes the woman, Tess D’Urberville, instead of the girl, Tess Durbeyfield.

Some of the critic’s views in the Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art could well be statements made regarding Tess of the D’Urbervilles also. They deem it a “pitiful but not hopeless story” (Saturday Review, 1913, p.557) of a couple who believed for years that there was “one who stood a bar to their marriage” (p.557) between them. Hardy, they say, is able to translate the coldest foundations of his works into a realistic, life-like understanding. They conclude:

“There is a solemn beauty in this little tale. It comes of a god-like sympathy with thwarted human loves, watching them as they refine under the harshness of fate, and find a comfort even in aspirations which they are unable to fulfil.” (Saturday Review, 1913, p.557).

The Academy and Literature critic corroborates this, stating that: “Fate plays with the characters, not blindly, but ingeniously and deliberately spoiling their chances, and, even when a dreamy, restful, half-happy ending seems possible… reserving her sharpest stroke for an unexpected moment” (The Academy and Literature, 1913, p.592).

It is evident that Hardy’s intent focus on the romantic tragedies that occurred in his Arcadia of Wessex catapulted his stories to such a level of fame that their eventual ‘immoral’ contents were ultimately forgiven by the masses, whom the Tillotson’s did not believe would be appreciative of such explicit themes.

Bibliography

A Changed Man. (1913) Saturday review of politics, literature, science and art, 116(3027), pp.556-557.

A Changed Man, The Waiting Supper, and Other Tales; concluding with The Romantic Adventures of a Milkmaid. (1913) The Academy and literature, 1910-1914, (2166), pp.592-593.

Allingham, P., (n.d.) A Chronology of the Life and Works of Thomas Hardy. [Online] Victorianweb.org. Available at: <https://victorianweb.org/authors/hardy/pva54.html> [Accessed 15 April 2021].

Brandwood, N., (2009) Treasure trove of letters from great authors who used to write for The Bolton Evening News | The Bolton News. [online] Theboltonnews.co.uk. Available at: <https://www.theboltonnews.co.uk/news/17530098.amp/> [Accessed 15 April 2021].

Hartrick, A. S. (1900) “I’m – afraid – you’ll have to send for a hurdle,” he went on feebly. The Sphere 28 April 1900, p. 451. Image scanned by Philip V. Allingham [Online] <https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/hartrick/2.html> [Accessed 29 April 2021].

Hilliard, C., (2009) The Provincial Press and the Imperial Traffic in Fiction, 1870s–1930s. Journal of British Studies, 48(3), pp.653-673.

Macmillan, (1929) The Map of Hardy’s Wessex from the Macmillan edition of Under the Greenwood Tree.. [image] Available at: <https://www.fulltable.com/vts/h/hwess/hw.htm> [Accessed 15 April 2021].

Tillotson & Son, (1987) Letter from Tillotson & Son to Thomas Hardy suggesting Hardy writes another novel as long as The Woodlanders and offering a thousand guineas for serial rights, 16 March 1887. [Online Image] Available at: <http://hardycorrespondents.exeter.ac.uk/text.html?id=dhe-hl-h.5559> [Accessed 15 April 2021].